Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony no. 4 in Fm, op. 36

another symphony of fate, but also drunkenness and triumph

performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Riccardo Muti

Photo by Vika Strawberrika on Unsplash

Preparing to teach this piece in a lecture last year gave me a totally new appreciation for Tchaikovsky in a symphonic context. I use his symphonies and concertos as examples of how I feel that Tchaikovsky’s strengths in lyricism and melody don’t do him as many favors in symphonies, his efforts in the forms I didn’t find very convincing at times.

They were pieces that I binged on early in my music days, the fourth and fifth symphonies especially, along with the (first but not only) piano concerto. In short order, though, I fell tired of them, feeling that their most obvious strengths lay in juicy melodies, beautiful tunes, and rich Russian orchestration. So I came to find them maudlin and somewhat boring, to be honest. That was the trajectory of some of the music I listened to in my very early days: immediately, richly satisfying and lyrical and juicy and showy, but then… that doesn’t last for me and I began to neglect them.

It starts to feel like the stories that a (grand)parent or someone tells you over and over that you know by heart, every pause, every turn, every beat. It might be charming at first, but at some point there’s no more itch to scratch because now it’s raw.

And then last year I decided to program this piece for one of my music lectures and decided to do some real research on it beyond just “what are the sections of the sonata form structure?” and rather than transcribing the video, here was my main source of info:

This analysis (I believe in four parts) gave me enough to notice and latch onto in the piece beyond “Oh how pretty!” that allowed me to do some deeper, more intentional listening. So in brief, what’s going on? (Because like Beethoven’s fifth, this is just not a piece that I could possibly have anything new to say about for how much it’s been analyzed and written about.)

The Background

The piece was written between 1877 and 1878, around the time when his patroness Nadezhda von Meck entered his life, and she is the work’s dedicatee: “My best friend.” She asked him to write a program for the work, a story or narrative for it, but this was later jettisoned in favor of letting the music do its thing. It was first performed in February 1878 at a Russian Musical Society Concert.

The Music

It’s somewhat fitting that we did Beethoven’s fifth just last month because to oversimplify it, these are both ‘fate’ symphonies. What’s that mean?

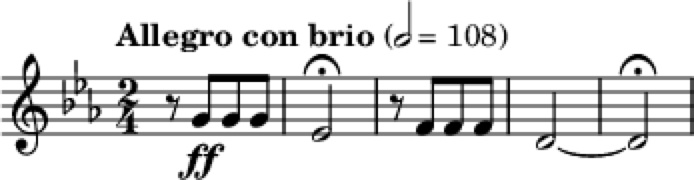

Well, not only is fate or struggle in life sort of the overarching theme, the human effort to find joy, etc., but both symphonies present a motif that represents that concept:

For Beethoven, it’s the famous rhythm everyone knows. For Tchaikovsky, it’s the beautiful and alarming horn call in a figure that also includes a triplet akin to Beethoven’s. Like Mahler 6, which we’ll also eventually get to, this motif, a musical character, really, appears not only at the beginning of the first movement, or even throughout the first movement, but belongs to the piece as a whole.

We talked about this back in September in our very first concert program when I wrote about Schumann’s second symphony. There are musical ideas, story arcs, characters, that belong perhaps to just one movement, or even only a portion of a movement, but there are others that belong not to one movement but to the symphony as a whole.

Beethoven weaves and adapts and varies this unifying fate motif that carries the theme of the work to its great, triumphant climax in the finale, and we have something of a similar narrative or trajectory here with Tchaikovsky.

There are waltz-like elements in parts of the first two movements, especially the second, and Tchaikovsky’s Russian elegance calls to mind the opulence of Anna Karenina-style ballrooms and palaces and extravagance that are shiny and showy enough to hide, even if for a bit, the sadness and tragedy of life that lies behind it all.

The third movement is what I hinted at in the subtitle at the top about drunkenness. Listen to Schwarz’s explanation of the work and how vastly different this third movement is from the prior two. It’s hushed, with only plucked strings, soft but crisp textures, subtle and playful and quiet, that is until the trio breaks out with what does feel like a group of drunken bandmates spilling out into the street long past midnight and goofing off as they play snippets of tunes that come to mind.

Not only is this a great departure from the depth and seriousness and richness of what came before, but once the trio is over, we’re lulled into the whispers again before the real literal breathtaking explosion of the finale. This effect is not an accident, for it makes the thunderous crash and seeming celebratory nature of the finale all the more grand.

However, I leave it to you to decide whether the joy expressed here is truly a triumph over fate and an attainment of happiness, or just a better attempt at ignoring the place that tragedy has in human life. I find Beethoven’s finale to be one of the most compelling things in music, but Tchaikovsky… you decide.

Coda

That’s all from Tchaikovsky for now, but there will be more Russian music to come in a couple of months. Please enjoy the music and we’ll see you later in the month for another Scandinavian program.